Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton is undoubtedly one of history’s most prominent explorers, and remains a principal figure of the period most commonly referred to as the ‘Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.’ He was an Anglo-Irish explorer who looked to further mankind’s knowledge surrounding Antarctica.

- Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton

He was born in Kilkea, County Kildare, Ireland, but he moved to London with his family at the age of ten. His first ever taste of Antarctic exploration came between 1901 to 1904, and he was the third officer on Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s Discovery expedition, but was eventually sent home on health grounds. Prior to this, Shackleton and his companions, Scott and Edward Adrian Wilson, set a new southern record by reaching latitude 82°S. The Discovery expedition was known officially as the British National Antarctic Expedition, and was aimed to gain understanding surrounding the icy territory’s biology, zoology, geology, meteorology and magnetism. During this expedition, snow-free Antarctic valleys were discovered, and these subsequently included Antarctica’s longest river. Furthermore, the expedition came across the Cape Crozier emperor penguin colony, King Edward VII Land, and the Polar Plateau, where the South Pole is located. The Discovery expedition attempted to reach the South Pole, but the furthest point they reached was 82°17S. As an entirety, the expedition served as a stepping stone for many future British expeditions, and was a significant landmark in the exploration of Antarctica.

To fully understand the exploration of Antarctica, one must be familiar with the term ‘Farthest South.’ This refers to the most southerly latitude reached by explorers prior to the first ever successful expedition to the South Pole itself, in 1911. Many world-famous voyagers attempted this feat; Ferdinand Magellan, Sir Francis Drake, and Captain James Cook. However, the most significant clump of progress was made during the ‘Heroic Age.’

- Farthest South

After staking his claim in the Farthest South achievement in the Discovery expedition, Shackleton suffered from a collapse during the journey home. Captain Scott ordered that he be taken home, and Shackleton resented him for this. The two would go on to establish a bitter rivalry.

Sir Shackleton’s next expedition was the Nimrod expedition, which took place between 1907 to 1909. He organised it himself, and it was the first ever expedition to set the definitive objective of reaching the South Pole. Whilst he didn’t reach the South Pole itself, he did break his own record and managed to reach Farthest South latitude at 88°S, which is just 112 miles away. Whilst this might sound like incredibly far away, and perhaps even a failure, one must consider the difficulties Shackleton would have faced in the early 20th Century.

The process of choosing crew members was extremely selective, as it should be. Shackleton settled on: Frank Wild and Ernest Joyce, the two petty officers from the Discovery expedition, Jameson Boyd Adams; a Royal Naval Reserve lieutenant, and the eventual meteorological expert was also to be in the crew. Rupert England was another addition; another naval reserve officer, would go on to be chief officer. Sir Philip Brocklehurst was to be the assistant geologist, and a shore party consisted of Aeneas Mackintosh, Alistair Mackay and Eric Marshall. Shackleton hand-picked Bernard Day to be the motor expert.

Finally, the scientific team needed to be put together. Sir Shackleton recruited James Murray, an English biologist, as well as a very young Raymond Priestley, who was just twenty-one years old at the time. Shackleton saw his brilliance even then, and Priestley would go on to be a founder of the Scott Polar Research Institute.

Shackleton’s final two additions to the team were made in Australia. The first of which was Edgeworth David; a successful professor of geology at the University of Sydney; he would be employed as the party’s chief scientific officer. The latter was an ex-pupil of Edgeworth David; Douglas Mawson. He was a lecturer in mineralogy at the University of Adelaide. Both Australians initially intended to sail to Antarctica and then instantaneously return with Nimrod, however, Shackleton eventually managed to persuade them to become full-time members of his team.

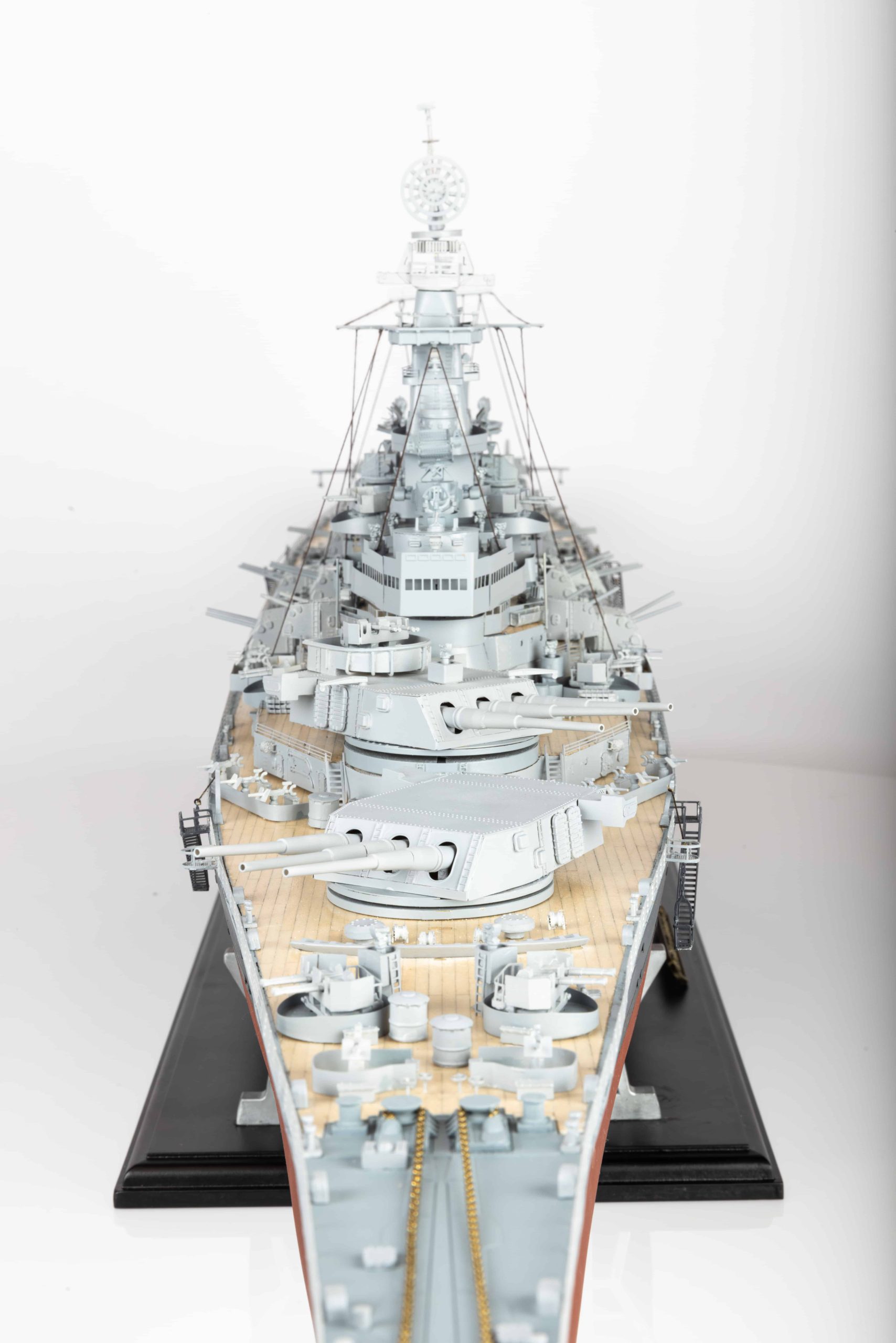

Exhaustive levels of time and effort were poured into the planning of the Nimrod expedition. Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton used mixed transport methods, including the use of Manchurian ponies as pack animals, and the more conventional dog sleds. Sir Shackleton was also given the opportunity to take a specially adapted motor car, which was extremely rare and highly expensive. However, he would have had minimal support, difficult navigation methods, and would have to face the cold, harsh weather.

- Shackleton's Planned Route

Another major achievement of the Nimrod expedition was the ascent of Mount Erebus. After the departure, a sizable block of sea ice broke up and severed Shackleton’s route to the Barrier, rendering any potential depot-laying utterly impossible. To provide the expedition with some much-needed impetus, he immediately ordered an attempt to ascend Mount Erebus, which measured at 12,450 feet high, and had never been climbed before.

On the 7th March 1908, two groups combined at an altitude of 5,500 feet, before advancing towards the summit. They were instantly faced with problems, as an awry blizzard postponed their push until the 9th. On this day, the climb resumed, and they reached the summit of the lower, main crater. However, by this time, a member of the team, Sir Philip Brocklehurst, the assistant geologist suffered from severe frostbite to both feet. The party left him in their camp whilst they continued their ascent, and they reached the active crater after a further four hours’ worth of climbing. They carried out numerous meteorological and geological experiments, and they ensured to take rock samples for extensive studying. By this point, all members of the party were frostbitten, fatigued, starving and parched, so they swiftly descended Mount Erebus by sliding down successive snow-slopes; risky but ultimately necessary were they to stay alive. They managed to reach the Cape Royds hut on March 11th, with all of them “nearly dead” according to another climber in the team, Eric Marshall.

- Mount Erebus

Sir Ernest Shackleton had predicted that the winter of 1908 would be particularly treacherous, and so the decision was made to remain in camp and resume their journey south before the New Year. They occupied a prefabricated hut measuring in at around 33 by 19 feet. To reduce demarcation between upper and lower decks, Shackleton made sure of the fact that everybody lived, ate and worked together. This kept morale high, but also prevented any ideals of favouritism. The hut was divided into a series of two-person cubicles, alongside a kitchen area, a darkroom, storage space and even a laboratory. There were also in-built stables for the ponies, and a kennel for the dogs, both heated and sheltered. Shackleton’s leadership style was highly inclusive, and couldn’t be more different from his rival’s, Captain Scott. As previously mentioned, this meant no division and so sprits were high. An account of Brocklehurst’s diary stated that “Shackleton had a faculty for treating each member of the expedition as though he were valuable to it.” This philosophy ensured each member was kept happy, and actually respected Shackleton. The expedition was theirs, not just his, and this kept them together until the end.

During this winter, Joyce and Wild managed to print thirty copies of the expedition’s book; Aurora Australis. This was the first-ever book written, printed and illustrated in Antarctica. It was bound and sewn through the use of discarded packaging materials, and this sort of efficiency was essential in the success of Shackleton’s expedition. Shackleton himself spent the majority of the winter preparing for the upcoming season, and their journey south. The two major objectives were reaching the South Pole, and the South Magnetic Pole. He knew that by making his base in McMurdo Sound, the goal of getting to the Magnetic Pole was achievable once more. Whilst the winter was largely a success, Shackleton did suffer a few significant setbacks, the most important being the death of four ponies. They perished after eating volcanic sand, which was extremely high in salt content.

Due to the limited number of surviving ponies, Shackleton decided on a four-man team for the journey south. His experience from the Discovery expedition led him to putting his faith in ponies rather than dogs, which he was now ultimately regretting, but of course, this wasn’t going to stop him now. Furthermore, the motor car was not a viable option. It ran well on flat ice, but was practically obsolete when faced with Barrier surfaces.

Shackleton’s decided that the three men who would join him on his journey south would be Eric Marshall, Jameson Boyd Adams and Frank Wild. Ernest Joyce was seriously considered, as he did have more Antarctic experience than Marshall, however, he was eventually deemed unfit after a medical examination.

The four men began their march south on the 29th October 1908. The return distance to the Pole was calculated to be 1,719 miles. His first draft of the plan allowed 91 days for the journey back, which would require the team to travel an average distance of 18 miles a day. However, immediate difficulties were unearthed; poor weather and weakness in the ponies were most notable. Therefore, Sir Ernest Shackleton reduced the daily food allowance and extended the journey time to 110 days. This meant the team only had to average around 15.5 miles a day.

Incredible levels of progress were made between the 9th and the 21st November; however, Shackleton knew this was the calm before the storm. The ponies suffered greatly on the tricky Barrier surface, and the first of the four had to be shot out of mercy, at 81° S.

The mood was lightened five days later, on the 26th. They broke the farthest south record, establishing their position and passing the 82° 17’ mark set by Scott in December 1902. Shackleton’s was significantly more impressive though, as his crossed the distance in just 29 days, compared to Scott’s 59.

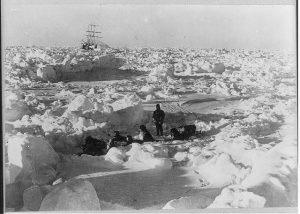

As the four men journeyed further into uncharted territory, the Barrier surface became increasingly dangerous. Two more ponies succumbed to the struggles and died, leaving one left standing. Westward mountains curved round which blocked their southbound route, but the party’s attention was diverted by a “brilliant beam of light” in the sky. Not Northern Lights, but shimmering from a great glacier that they would christen as “Beardmore” a few days later, on the 3rd December, after the expedition’s most prominent sponsor.

- An example of the treacherous terrain Shackleton's team had to face

The final pony was named Socks, and travel on the surface of the glacier proved to be the final straw for him. He found great difficulty in securing his footing, and disappeared down a crevasse on the 7th December, almost taking Frank Wild with him. For the remainder of the journey, the four men had to continue with nothing but each other, and their supplies which they hauled themselves.

Tensions were running high amongst the four men. Wild privately confessed that he wished Marshall would “fall down a crevasse about a thousand feet deep.” Marshall wrote that “following Shackleton to the Pole was like following an old woman. Always panicking.”

They did celebrate Christmas Day together, sharing cigars and crème de menthe. On this day, their position was marked as being 85° 51’S, which was still a humongous 287 miles from the Pole. They had just a month’s supply worth of food left, were frostbitten and miserable, and all extremely fatigued. Shackleton wasn’t ready to admit defeat yet, though, and cut food rations further, dumped all but the most essential equipment, and ordered that they continue onward.

Ascent of the glacier was completed on Boxing Day, and the four men began marching on the polar plateau. Conditions only worsened, with Shackleton claiming that New Year’s Eve was “the hardest day we have had.” However, on New Year’s Day, he recorded that they had beaten both the North and South polar records, reaching a position of 87° 6.5’ S. Tensions were higher than ever, with Wild writing “…if only we had Joyce and Marston here instead of those two (Marshall and Adams) grubscoffing useless beggars, we would have done it easily.”

It was on the 4th January 1909, when Sir Shackleton could take no more, and finally resigned to the fact that the Pole was out of their reach. He therefore revised his goal, and established it as being within 100 geographical miles of the Pole. They struggled onwards, on the verge of death, becoming more and more hostile towards each other as the days passed. However, on the 9th January, without the sledge or any other equipment whatsoever, they reached 88° 23’ S – just 97.5 geographical miles from the South Pole. Shackleton and his team had done it, and they accordingly planted the Union Jack in the ground, and named the polar plateau after King Edward VII.

Shackleton began the long journey home, with multiple members of the team ill, weak and fatigued. Rations were scarce, supplies were run thin, and all crew members were barely alive, breathing raggedly and hardly conversing at all. However, Adams recalled that “the worse he (Shackleton) felt, the harder he pulled.” This fighting spirit set an example for the rest of his team, and they finally managed to reach the familiar Bluff Depot on the 23rd February. Food supplies were restocked, medicine was passed around, and new clothes were available to the four men. This greatly lifted spirits, however, they still had to get back to Hut Point before March 1st. Eventually, they reached it on the 28th February. It wasn’t without its struggles, as Marshall had collapsed the day before, and so Wild and Shackleton rushed to Hut Point and set fire to a wooden hut, gaining Nimrod’s attention. Three days later, all four men were onboard the ship, and they were given the green light to push north.

It was on the 23rd March 1909, that Shackleton landed in New Zealand. He cabled a 2,500-word report to the Daily Mail in London. He immediately received praise from the exploring community, but wasn’t without his fair share of critics. Many expressed their disbelief at the latitude recorded, due to the fact that it was logged by dead reckoning; through direction, speed and elapsed time.

Regardless of his doubters, Shackleton arrived at London’s Charing Cross Station on June 14th and was met by an enormous crowd, which even included Captain Scott, who was admittedly jealous and reluctant.

Shackleton was made a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, by King Edward VII, and he was later given a knighthood. The Royal Geographical Society presented him with a gold medal, but were hesitant and openly claimed it wasn’t going to be as large or grand as the one awarded to Captain Scott. The public didn’t care; Shackleton was the hero.

His farthest south record was broken only three years later, on the 15th December 1911. Roald Amundsen reached the South Pole itself. However, both Shackleton and Amundsen held a mutual respect for one another, heralding the other’s achievements.

After this, Shackleton became fixated on the idea of transcontinental crossing, particularly with the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914 to 1917. This was largely a failure, however, Shackleton’s status as a prominent figure in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was already cemented for all-time, as were the statuses of his crew members.

Numerous expeditions were carried about by Shackleton for the remainder of his life, until his untimely death on the 5th January 1922. He suffered a fatal heart attack in South Georgia, after complaining about back pain and other discomfort for several weeks. His story is one of perseverance and determination. He suffered an enormity of setbacks, struggles and had to adapt several times. He is undoubtedly one of the most important explorers of all-time, and set a terrific example of how to keep a crew together, even through the harshest conditions.

- Jack Ratledge

Customer Reviews

Information

My account

Legal

Follow Us

Follow us to keep up-to-date using our social networks

Copyright © 2024. Premier Ship Models. All Rights Reserved.