Officially, the Marie Celeste was actually called the Mary Celeste, and before that it was christened as the Amazon. The Marie Celeste was a fictional ship created by Arthur Conan Doyle, author of Sherlock Holmes, and the Marie Celeste was inspired by the real-life counterpart, the Mary Celeste. Very confusing!

It was an American merchant brigantine which was discovered adrift, mostly intact and undamaged, but with every member of the crew missing. The lifeboat was gone, and so many people assumed they had fled via lifeboat, however, not a single crew member was ever seen or heard from again.

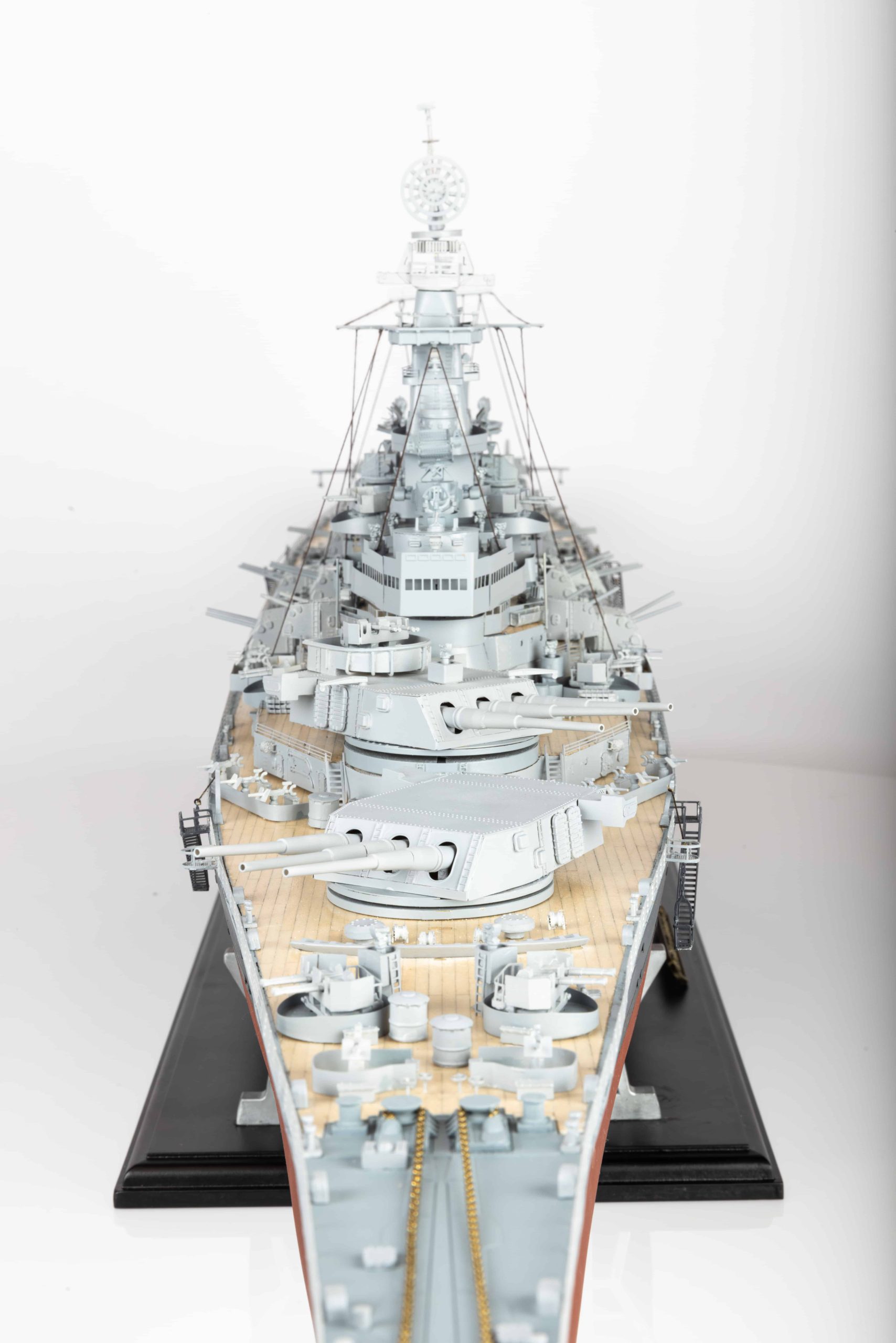

In late 1860, at the shipyard of Joshua Dewis in the village of Spencer’s Island, Nova Scotia, the keel of the Mary Celeste was laid. The keel is the lowest longitudinal structural element on a watercraft, and is often the foremost foundation before construction can begin. It was built from locally felled timber, alongside two masts, and it was rigged as a brigantine. The Mary Celeste was carvel-built, which means that the hull planks were laid edge to edge and fastened to a rigid frame, forming an extremely smooth and watertight surface. With the planks flush as opposed to overlapping, the ship was billed as being more secure and reliable than most others. Launched as the Amazon on May 18th 1861, the ship was registered at Parrsboro, a small community in Cumberland County. The Mary Celeste was a fairly large sized ship at the time, and was owned by a consortium of nine people. The ship’s first captain was Robert McLellan, and he was one of the co-owners.

- Spencer's Island, Nova Scotia

Strange happenings surrounding the Mary Celeste began shortly after its maiden voyage. In June 1861, the Amazon sailed to Five Islands, Nova Scotia, with the objective of taking on a load of timber for passage to London. After overseeing the ship’s cargo being brought onboard, Captain McLellan fell gravely ill, and his condition would only worsen. The Amazon returned to Spencer’s Island shortly after, and Robert McLellan would go on to be the first of three captains to die aboard the Mary Celeste.

With the main objective of finishing the journey to London, John Nutting Parker usurped the role of captain. The Amazon would only face more adversity; colliding with fishing equipment and even crashing into another brig in the English Channel, and subsequently sinking it completely. Parker remained as captain for a couple of years, and the Amazon primarily operated in trade in and around the West Indies under his command.

After Parker, the role of captain was filled by William Thomspon, and he remained in charge until 1867. These four years served as a quiet period for the Mary Celeste, until a storm wrecked the ship off of the coast of Cape Breton Island in early October, and the crew were forced to abandon.

Within the month, the ship was bought as a derelict by Alexander McBean, a resident of Glace Bay, Nova Scotia. He sold it on to a local businessman, who subsequently sold it to Richard W. Haines, a mariner from New York. He spent a little over $1000 to purchase the wreck, and a further $9000 restoring it. Haines then commissioned himself as the captain, and renamed the Amazon to the Mary Celeste.

It was just a couple of years later, in October 1969, that the ship was seized by Haines’s creditors. It was sold to a New York consortium, which was headed by a man called James H. Winchester. There is no historical record of the trading activities of the Mary Celeste between 1869 and 1872, and some conspiracy theorists have seen this as something more sinister, regarding alleged organised crime and ‘unofficial operations.’

In early 1872, the Mary Celeste underwent extensive restoration, enlarging her significantly. Another deck was added, and lots of the timber was replaced, resulting in the ship being heavier. The ship’s new captain was a member of the consortium, Benjamin Spooner Briggs. He would go on to be the captain who was supposed to be manning the ship off of the coast of Portugal, on December 4th 1872. Instead, this was when it was discovered adrift, with no signs of violence, mutiny, struggle, or foul play. The Mary Celeste was simply mindlessly drifting across the ocean, as though nothing was wrong.

Benjamin Briggs was a devout Christian man who had been born to a sailing father, Nathan Briggs. He married his cousin, Sarah Elizabeth Cobb, which wasn’t unusual at the time, and went on to have two children with her; Arthur and Sophia. Briggs was a man who took pride in his profession, and was looking to retire from the sea to start a business with his brother, Oliver. However, this plan never came to fruition. Rather than investing into a business, they each bought shares of a ship, with Oliver buying stakes in Julia A. Hallock, and Benjamin investing in the Mary Celeste.

October 1872; Briggs was set to take command of the Mary Celeste for her maiden voyage following the lengthy refurbishment she had undergone in New York. The destination was Genoa, Italy, and Briggs had arranged for his wife and daughter to accompany him, whilst his son, Arthur, would stay home with his grandmother.

The process of choosing a crew for a ship is always done with meticulous care and precision. Briggs made no exception. The first mate, Albert G. Richardson, was married to a niece of Winchester, and had even sailed with Briggs before. The second mate was a young New York local, Andrew Gilling, whom people described as kind and affable. The steward was a newly married man, Edward William Head, who had been personally recommended to Briggs via Winchester. Finally, the four general seamen were all German men. Two brothers; Volkert and Boz Lorenzen, Arian Martens and Gottlieb Goudschaal. Testimonials described the men as peaceful, and utterly professional sailors. Briggs had even written a letter to his mother shortly before the voyage, declaring his happiness regarding the crew. Sarah said to her own mother that the crew were capable and competent. This threw many people off when assuming the ship had seen mutiny or violence, as the internal relationships between all members of crew seemed eminently positive.

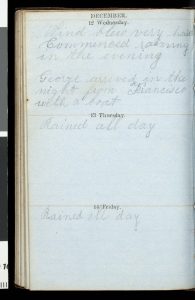

- An account from Briggs’ diary, recounting the weather. This shows the normality of their journey so far.

On October 20th 1872, Briggs arrived at Pier 50, which is located on the East River in New York City. Briggs was to supervise the loading of Mary Celeste’s cargo, which was over 1,700 barrels of denatured alcohol. Some theories suggest the alcohol was the root cause of the crew’s disappearance, as it could have been poisonous. Had the crew been poisoned, it was unlikely that there would be any blood or signs of violence, however, that doesn’t answer the query of their disappearance.

Over a week later, on November 3rd, Briggs sent a letter to his mother declaring his pride concerning the Mary Celeste. He is quoted as saying via script, “Our vessel is in beautiful trim and I hope we shall have a fine passage.” Yet again, Briggs seemed in good spirits. The ship’s condition was exceptional. There were no signs hinting towards their inevitable demise just a month later.

On the morning of November 5th, Mary Celeste departed from Pier 50 and moved into the New York Harbour. With uncertain weather, Briggs make the decision to wait until the seas were calmer. Anchoring the ship off of Staten Island was his next move. His wife, Sarah, used the suspension in the voyage as an opportunity to send one final letter to her mother-in-law. It was notably ominous, and some conspiracy theorists believe Sarah knew of potential foul-play in the coming weeks. She is stated as saying, “Tell Arthur I make great dependence on the letters I shall get from him, and will try to remember anything that happens on the voyage which he would be pleased to hear.” With the weather easing just a couple of days later, the Mary Celeste pushed on into the Atlantic.

Now, Sarah’s words are clear. She evidently missed her son, and wanted to see him again, ideally sooner rather than later. However, her strangely specific mention of trying to remember happenings whilst on the voyage threw many historians off. What would cause her to potentially forget any key events? And she wanted her son to know how much his letters to her meant, almost as if she knew she wouldn’t see him again, and wanted to reinstate her love for him one last time.

Nearby, in Hoboken, New Jersey, a Canadian brigantine by the name of Dei Gratia lay in waiting. Translated from Latin to mean, ‘By the Grace of God,’ the ship’s name is all too ironic, as it would discover the derelict Mary Celeste adrift off of the Portuguese coast just a few weeks later. It’s was manned by Captain David Morehouse, and his first mate Oliver Deveau. They were two Nova Scotians who were highly respected in the sailing and maritime industry, and some writers think it’s highly possible that both Morehouse and Briggs knew each other, and may have even been friends. However, due to a lack of comprehensive evidence, it’s hard to make a substantial claim or judgement. What is suspicious is that there are accounts of Morehouse and Briggs meeting for dinner on the night before the Mary Celeste’s departure, and this leaves lots to the imagination. Perhaps Morehouse had been planning something more sinister all along, but again, that is nothing more than a theory, and much like the rest of the Mary Celeste and its accompanying stories, is utterly shrouded in mystery.

It was midday, on December 4th 1872, when the Dei Gratia spotted a ship heading towards them, about six miles out. The ship’s course was unsteady, as was the arrangement of its sails. After attempting to signal, and subsequently receiving no response, Morehouse thought it wise to approach the ship as he suspected something was wrong. When the mysterious vessel was within boarding distance, Morehouse noticed nobody was on deck, and so he sent his first and second mates, the aforementioned Oliver Deveau, and John Wright, to investigate the ship. Both sailors quickly recognised the watercraft as Briggs’ Mary Celeste, but were left with an unsettling feeling deep in their stomachs, and a (albeit clichéd) chill down their spines.

Upon noticing the poor conditions of the sails, Wright allegedly became nauseous and uneasy, with Deveau experiencing a similar sensation. Some sails were missing altogether, and ropes were strewn haphazardly over the sides. Of the three hatches, the main hatch cover was secure, whilst the fore and lazarette hatches were left open. The only lifeboat on the ship was completely missing, and so the crew of the Dei Gratia were hoping the Mary Celeste’s men had fled, and would be found later. However, neither the men nor the lifeboat were ever discovered.

Deveau and Wright continued investigating the Mary Celeste. They found that the ship’s compass had moved from its place slightly, with the glass broken, and there was over a metre of water in the hold. Whilst this level is significant, a ship of the Mary Celeste’s size was (evidently) able to withstand this and continue sailing. A sounding rod used to measure water level was found on the deck, but from the looks of it had never reached the hold.

In the mate’s cabin, both of Dei Gratia’s men discovered the Mary Celeste’s log. Its final entry was dated nine days earlier, in the morning of November 25th. It noted nothing sinister, just the Mary Celeste’s position – 400 nautical miles away from where the Dei Gratia came across it. Deveau noted orderly interiors for all the cabins, albeit slightly wet. Personal items were scattered across Briggs’ personal cabin, however, everything else appeared to be in a neat fashion. There was a sheathed sword under Briggs’ bed, which wasn’t its original position, and the majority of the ship’s papers and navigational instruments were missing. All equipment was appropriately stowed, no food was being prepared but provision levels were sufficient, and there was absolutely no evidence of violence or a fire. This reinforced Deveau and Wright’s assumption that the Mary Celeste’s crew had fled via the single lifeboat.

Deveau returned to the Dei Gratia and reported all of this information to Morehouse. The captain decided to bring the abandoned Mary Celeste to Gibraltar, which was 600 nautical miles away. Maritime law states that a salvor (somebody who recovers a derelict ship or wreckage) can expect a sizable share of the resources and cargo onboard the ship they discovered. Combining this law with Morehouse’s dinner with Briggs, the Dei Gratia following the Mary Celeste’s path, and other small details have led people to theorise that Morehouse planned the Mary Celeste’s abandonment from the beginning, so he could claim its monetary value for himself and his crew.

Morehouse’s first mate, Oliver Deveau, was explicit in a letter he wrote to his wife, saying, “I can hardly tell what I am made of, but I do not care so long as I got in safe. I shall be well paid for the Mary Celeste.” This had led some to believe that Deveau was questioning his morality, perhaps after executing Morehouse’s sinister plan to claim the Mary Celeste’s goods as his own, yet he was happy to do so as it guaranteed him riches.

- The Mary Celeste's registry document

A couple of weeks later, the salvage court hearings began. The hearing was conducted by Frederick Solly-Flood, the Attorney General of Gibraltar. In historical accounts, Flood has been described as being a man “whose arrogance and pomposity were inversely proportional to his IQ, and the sort of man who, once he had made up his mind about something, couldn’t be shifted.” In other words, he was viewed as extremely stubborn and egotistical.

After listening to both Deveau’s and Wright’s testimonies, Flood was convinced that a crime had been committed, and the alcohol onboard was the sole cause of any potential violence. An investigation of the ship was carried out, and due to an upright vial of sewing machine oil, many ruled out the possibility of heavy weather. However, the vial could have simply been removed or replaced since the ship’s abandonment. There were possible traces of blood on Briggs’ sword, and stains on the deck, along with a deep mark in the timber on the deck which looked like it had been left by an axe of some kind. These all reinforced Flood’s belief that the ship’s abandonment was caused by human wrongdoing, rather than some kind of natural phenomena.

The head of the examination, John Austin, also noted cuts on each side of the bow. He thought it was deliberate, as they looked as though they had been done by some kind of sharp instrument. After reporting this to Flood, Flood sent the reports to the Board of Trade in London. His own conclusion denoted that the lesser crew members had gotten access to the alcohol, and subsequently murdered Briggs, his family and the officers in a drunken haze. They had then cut the bows to stage a collision of some kind, and fled the ship in the missing lifeboat. There were many holes to Flood’s conclusion; the most prominent being that the alcohol wasn’t potent, and so the crew couldn’t have gotten drunk if they had consumed it. Flood also had no explanation for the limited signs of violence, absence of cadavers and orderly nature of the ship’s belongings.

Flood did suspect that Morehouse and his crew were hiding something, more specifically the location of the Mary Celeste when they had found it, and the original contents of the log. He simply couldn’t accept that the ship had travelled 400 nautical miles without a crew, with no critical damage or signs of deterioration.

January came, and James Winchester arrived in Gibraltar. He countered the argument that Briggs could have possibly engaged his own crew, resulting in his death. He testified to Briggs high-character and morality, and that he would only ever abandon the Mary Celeste if there was no hope for it. Flood’s assumption of both mutiny and murder received further hindrances when the stains on the sword and the deck were scientifically proven not to be blood, and instead iron citrate. The sword had been cleaned with lemon, and some had possibly spilled onto the deck. Flood therefore released Mary Celeste from the court’s jurisdiction in late February, with a high level of reluctancy. However, he could do nothing. His theories had been largely disproven and he knew it.

Regardless of Flood’s failure to prove of foul-play in the hearing, public suspicion remained high. Some even believed that Morehouse had ambushed the Mary Celeste, lured Briggs and his crew aboard the Dei Gratia, and killed them aboard his own ship, before claiming the Mary Celeste as his own. However, this theory doesn’t account for the Dei Gratia’s slower speed, as well as the fact that they were a few days behind in terms of their voyage, and so could never have caught up to the Mary Celeste.

Others theorise more natural occurrences; potential swills in the ocean that threw the crew overboard, or a severe waterspout strike. In the event of the latter, that would explain the water in the hold, as well as the raggedy state of the sails and rigging. The sudden intake of water could also have led to the crew assuming that the Mary Celeste was sinking faster than it actually was. Some even believe that a seaquake could have damaged the cargo and subsequently released toxic fumes. Briggs then would’ve ordered total abandonment due to the concern of an explosion. Modern scientists have theorised that an explosion could have actually happened, but if it were butane gas, there would be no substantial evidence. A butane gas explosion would have resulted in a considerable blast and ball of flame, but no soot, scorch damage or even burning.

Of course, more outlandish theories also surround the fate of the Mary Celeste, ranging from seafaring ghosts, to sea monsters such as the Kraken, to pirates patrolling the coasts. Arthur Conan Doyle’s world-renowned retelling doesn’t adhere to the facts, and the ship is renamed to the Marie Celeste, but he writes about a story of murder and mutiny which many now believe to be true.

The Mary Celeste will forever be shrouded in secrecy, mystery and unanswerable questions. With its rich folklore, prevalent following and possibility for conspiracy, it’s one of the most popular items for conspiracy theorists to delve into, to this day, along the likes of Area 51, J.F.K’s assassination and the Moon Landing. It’s a ship synonymous with ghost tales, stories of mutiny and sinister happenings, and will forever be famous as an unsolvable mystery.

- Jack Ratledge

Customer Reviews

Information

My account

Legal

Follow Us

Follow us to keep up-to-date using our social networks

Copyright © 2024. Premier Ship Models. All Rights Reserved.